Preventing catastrophic pandemics

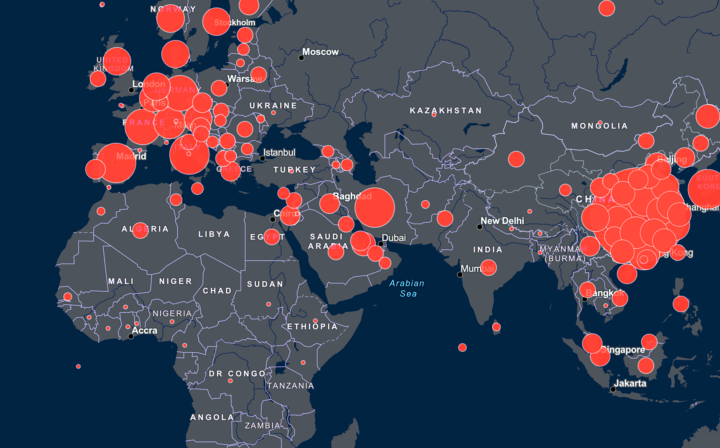

Some of the deadliest events in history have been pandemics.1 Due to developments in technology, as well as our growing interconnectedness, we face the possibility of future biological disasters that are even worse.

Global catastrophic biological risks (GCBRs) are risks of severe pandemics that are serious enough to threaten the future of humanity.

For reasons we discuss below, we think the chances of such a biological catastrophe are uncomfortably high. There are also a number of practical options for reducing these risks. So we think working to reduce GCBRs is a promising way to safeguard the future of humanity right now.

Note: This page gives a broad overview of the problem area and links to many resources on the topic. For an in-depth review of the issue and additional details about work in this area, see our full report on global catastrophic biological risks. (That report was published in March 2020 and largely written prior to the COVID-19 pandemic — but we think its conclusions still stand today.)

If you’re keen to work on this area in your career, we may also be able to help through our one-on-one advising.

Summary

Pandemics — alongside other global catastrophic biological risks, like bioterrorism or biological weapons — pose a substantial existential threat to humanity. As biotech progress continues, it looks increasingly plausible that it will become easier to manufacture extremely dangerous pathogens (whether deliberately or accidentally), potentially far worse than the SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes COVID-19.

We can prepare for the next pandemic — and hopefully head it off before it happens. We’re excited about a number of approaches to reduce these risks. For example, we could find technological solutions that make it easier to prevent and treat infections, and policy solutions that ensure countries and institutions respond better to pandemics. While there’s lots of work going on in this area, very little of this work is focused on the worst-case risks, and as a result, we think work to prevent potentially existential pandemics is highly neglected.

Our overall view

Recommended - highest priority

We think this is among the most pressing problems in the world.

Scale

Pandemics — especially engineered pandemics — pose a significant risk to the existence of humanity. We think there is a greater than 1 in 10,000 chance of a biological existential catastrophe within the next 100 years.2

Neglectedness

Billions of dollars a year are spent on preventing pandemics. Little of this is specifically targeted at preventing biological risks that could be existential — and we think that, if you care about future generations, it’s particularly important to try to reduce existential risks. As a result, our quality-adjusted estimate suggests that current spending is around $1 billion per year. (For comparison with other significant risks, we estimate that hundreds of billions per year are spent on climate change, while tens of millions are spent on reducing risks from AI.)

Solvability

There are promising existing approaches to improving biosecurity, including both developing technology that could reduce these risks (e.g. better bio-surveillance), and working on strategy and policy to develop plans to prevent and mitigate biological catastrophes.

Profile depth

Medium-depth

This is one of many profiles we've written to help people find the most pressing problems they can solve with their careers. Learn more about how we compare different problems, see how we try to score them numerically, and see how this problem compares to the others we've considered so far.

Table of Contents

Why focus your career on preventing severe pandemics?

Advances in biotechnology may pose catastrophic risks.

COVID-19 has highlighted our vulnerability to worldwide pandemics and revealed weaknesses in our ability to respond in a coordinated and sophisticated way. And historical events like the Black Death and the 1918 flu show that pandemics can be some of the most damaging disasters for humanity.

It is sobering to imagine the potential impact of a pandemic pathogen that is much more contagious than any we’ve seen so far, more deadly, or both.

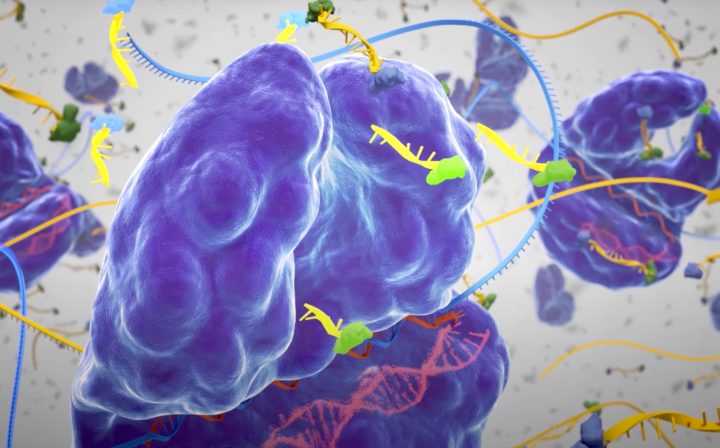

Unfortunately, the emergence of such a pathogen is not out of the question, particularly in light of recent advances in biotechnology, which have allowed researchers to design and create biological agents much more easily and precisely than was possible before. If the field continues to advance along this trend, over the coming decades it may become possible for someone to create a pathogen that has been engineered to be substantially more contagious than natural pathogens, more deadly, and/or more difficult to address with standard countermeasures.3

At the same time, it may become easier for states or malicious individuals to access these pathogens, and potentially use them as weapons, because the relevant technologies are also becoming more widely available and easier to use.4

Dangerous pathogens engineered for research purposes could also be released accidentally through a failure of lab safety.5

Either scenario could result in a catastrophic ‘engineered pandemic.’ Although making a pathogen as dangerous as possible will not generally be in the interest of states or other actors (in part because it would likely threaten their own forces), a purposefully engineered pandemic pathogen does have the potential to be significantly more deadly and spreadable. Possibilities of accidents, recklessness, and unusual malice suggest we can’t rule out the prospect of a pandemic pathogen being released that could kill a large percentage of the population.

How likely we are to face such a pathogen is a matter of debate. But over the next century the likelihood doesn’t seem negligible.6

Could an engineered pandemic pose an existential threat to humanity? Again, there is reasonable debate here. In the past, societies have recovered from pandemics as severe as the Black Death, which killed around a one-third to one-half of Europeans.7 But from what we’ve seen, the future GCBRs look like some of the larger contributors to existential risk this century.8

Reducing the risk of biological catastrophes by reducing the chances of potential outbreaks or preparing to mitigate their worst effects therefore seems very important.9

There are clear actions we can take to reduce these risks.

For example:

- Work with government, academia, and industry to improve the governance of gain-of-function research involving potential pandemic pathogens, commercial DNA synthesis, and other research and industries that may enable the creation of (or expand access to) particularly dangerous engineered pathogens. At times this may involve careful regulation.

- Strengthen international commitments to not develop or deploy biological weapons, e.g. the Biological Weapons Convention.10

- Develop broad-spectrum testing, therapeutics, and other technologies and platforms that could be used to quickly test, vaccinate, and treat billions of people in the case of a large-scale, novel outbreak.11

Learn more about these ideas and others in our interview with Dr Cassidy Nelson.

Most existing work is not aimed at reducing risks of the worst outcomes.

The broader field of biosecurity and pandemic preparedness has made major contributions to GCBR reduction. Many of the best ways to prepare for more probable but less severe outbreaks will also reduce GCBRs, so many people who are not concerned with GCBRs in particular still do work that is useful for reducing them. For this reason, we think advancing parts of the broader field — especially in areas like vaccine research or broad-spectrum treatments — can be very valuable, even from the perspective of just trying to reduce the chances or severity of the worst potential outbreaks.

There may be even more valuable opportunities. It seems to be relatively uncommon for people in the broader field of biosecurity and pandemic preparedness to aim their work specifically at reducing GCBRs. Projects that disproportionately reduce GCBRs also seem to receive a relatively small proportion of health security funding.12 In our view, the costs of biological disasters grow nonlinearly with severity because of the increasing potential for the event to contribute to existential risk. This suggests that projects that reduce GCBRs in particular should receive more funding and attention than they currently seem to.

Moreover, insofar as more targeted interventions would be useful (and we’d guess they would be13) the fact that there is comparatively little work targeted toward reducing GCBRs right now suggests that the area is somewhat neglected. This means that if you enter the field of biosecurity and pandemic preparedness aiming to reduce GCBRs, there may be particularly good opportunities to do so that others have not already pursued.

If you do enter the field aiming to reduce GCBRs, it might be easier to work on broader efforts that have more mainstream support first, and then transition to more targeted projects later.

If you are already working in biosecurity and pandemic preparedness (or a related field), this might be a good time to advocate for a greater focus on measures likely to help us with whatever outbreak surprises us next. There may be a greater openness to ideas in this area now, as people reflect on how underprepared we were for COVID-19.14

What kinds of work are most needed?

Biosecurity and pandemic preparedness are multidisciplinary fields. To address these threats effectively, we need at least:

- Technical and biological researchers to investigate and develop tools for controlling outbreaks, such as broad-spectrum testing and antivirals. (See examples of research questions.)

- Strategic researchers and forecasters to develop plans, such as for how to develop or scale up vaccines quickly.

- People in government to pass and implement policies aimed at reducing biological threats.

It’s also important to remember that this area involves information hazards, making it essential for people who can act with discretion to fill these roles. This also means that information security experts may be especially helpful in this area.

Example reader

What jobs are available?

There are many organisations and agencies that work on reducing biological threats. Here are some that work specifically on GCBRs:

- The Center for Health Security (CHS) received a $16 million grant from Open Philanthropy, who see CHS “as the preeminent U.S. think tank doing policy research and development in the biosecurity and pandemic preparedness (BPP) space.”

- The Future of Humanity Institute (FHI) at Oxford University conducts multidisciplinary research on how to ensure a positive long-run future. With the recent hire of Piers Millett, FHI is looking to expand its research and policy functions to reduce catastrophic risks from biotechnology.

- The Center for International Security and Cooperation has a biosecurity programme headed by Megan Palmer and was funded by Open Philanthropy.

The Nuclear Threat Initiative is a US non-partisan think tank that works to prevent catastrophic attacks and accidents with nuclear, biological, radiological, chemical and cyber weapons of mass destruction and disruption. See current vacancies.

- Intelligence Advanced Research Projects Activity (IARPA) is a government agency that funds research relevant to the US intelligence community. It has sponsored research on how to improve biosecurity and pandemic preparedness.

The Cambridge Centre for the Study of Existential Risk at Cambridge University houses academics studying both technical and strategic questions related to biosecurity. See current vacancies.

- Bipartisan Commission on Biodefense is a group that analyses the United States’ defence capabilities against biological threats, and recommends and lobbies for improvements.

- Global Catastrophic Risk Institute is an independent research institute that investigates how to minimise the risks of large-scale catastrophes. See current vacancies.

We list particular jobs related to reducing biological threats at these organisations and others on our job board:

Our job board features opportunities in biosecurity and pandemic preparedness:

Want to work on reducing risks of the worst biological disasters? We want to help.

We’ve helped people formulate plans, find resources, and put them in touch with mentors. If you want to work in this area, apply for our free one-on-one advising service.

Want to support work in this area by donating?

You can also help by donating to well-run organisations that are making important progress on this issue.

Which organisations should you give to? We haven’t investigated this question ourselves, but we asked a couple of advisors working on biosecurity and pandemic preparedness for their suggestions.

Two organisations seem to stand out as particularly good giving opportunities:

Open Philanthropy, a foundation that broadly shares our values, has made grants to both of these organisations based on assessments of the quality of their work, staff, and structure; their global influence; and how they are likely to use the grant.

However, both organisations might still have room for more funding.15 You can help fill any gaps by ‘topping up’ Open Philanthropy’s grants with your own donations.16 (Disclosure: Open Philanthropy is our single largest funder.)

To learn more, read Open Philanthropy’s assessment of these organisations and their specific justifications for making NTI a grant of $6 million and CHS a grant of $16 million, both in 2017.

Learn more

Articles and podcasts

See our full profile on GCBRs and how to reduce them, and our interview with the profile’s author, Greg Lewis:

Or listen to an audio version of the article:

We also have several other podcast episodes that discuss GCBRs and strategies for reducing them:

Books

Two books we especially recommend on biological disasters:17

- Biosecurity Dilemmas: Dreaded Diseases, Ethical Responses, and the Health of Nations by Christian Enemark

- Deadly Companions: How Microbes Shaped Our History by Dorothy Crawford

Other resources:

On GCBRs and how to reduce them

- Chapters 3 and 5 of Toby Ord’s book The Precipice: Existential Risk and the Future of Humanity, which discuss the threat of engineered pandemics and other biological threats (2020)

- Podcast: Engineering the Apocalypse with Sam Harris (2021)

- First working definition of Global Catastrophic Biological Risks from CHS

- Engineered pathogens: The opportunities, risks and challenges by Cassidy Nelson in The Biochemist (2019)

- What rough beast? Synthetic biology, uncertainty, and the future of biosecurity by Gautam Mukunda, Kenneth A. Oye, and Scott C. Mohr (2009)

- Horsepox synthesis: A case of the unilateralist’s curse? by Gregory Lewis in The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists (2019)

- Information Hazards in Biotechnology by Gregory Lewis, Piers Millett, Anders Sandberg, Andrew Snyder-Beattie, and Gigi Gronvall (2019)

- Bridging Health and Security Sectors to Address High-Consequence Biological Risks by Cassidy Nelson and Michelle Nalabandian (2019)

- The Precipice‘s appendix, which lists policy and research ideas for reducing existential risks, including from GCBRs

- Greg Lewis’s ultra-rough reading list on GCBRs

- A list of resources, including community discussion groups in different areas from Effective Altruism London

Resources for general pandemic preparedness:

- The Characteristics of Pandemic Pathogens from CHS (2018)

- Modernizing and Expanding Outbreak Science to Support Better Decision Making During Public Health Crises: Lessons for COVID-19 and Beyond from CHS (2020)

- UK Government’s approach to emerging infectious diseases and bioweapons by Nelson et al. (2019)

- The Global Health Security Agenda

- Some good online sources to keep abreast of developments in the field (primarily from a US perspective) are the GMU Pandora report and the CHS mailing list.

Career resources

Notes and references

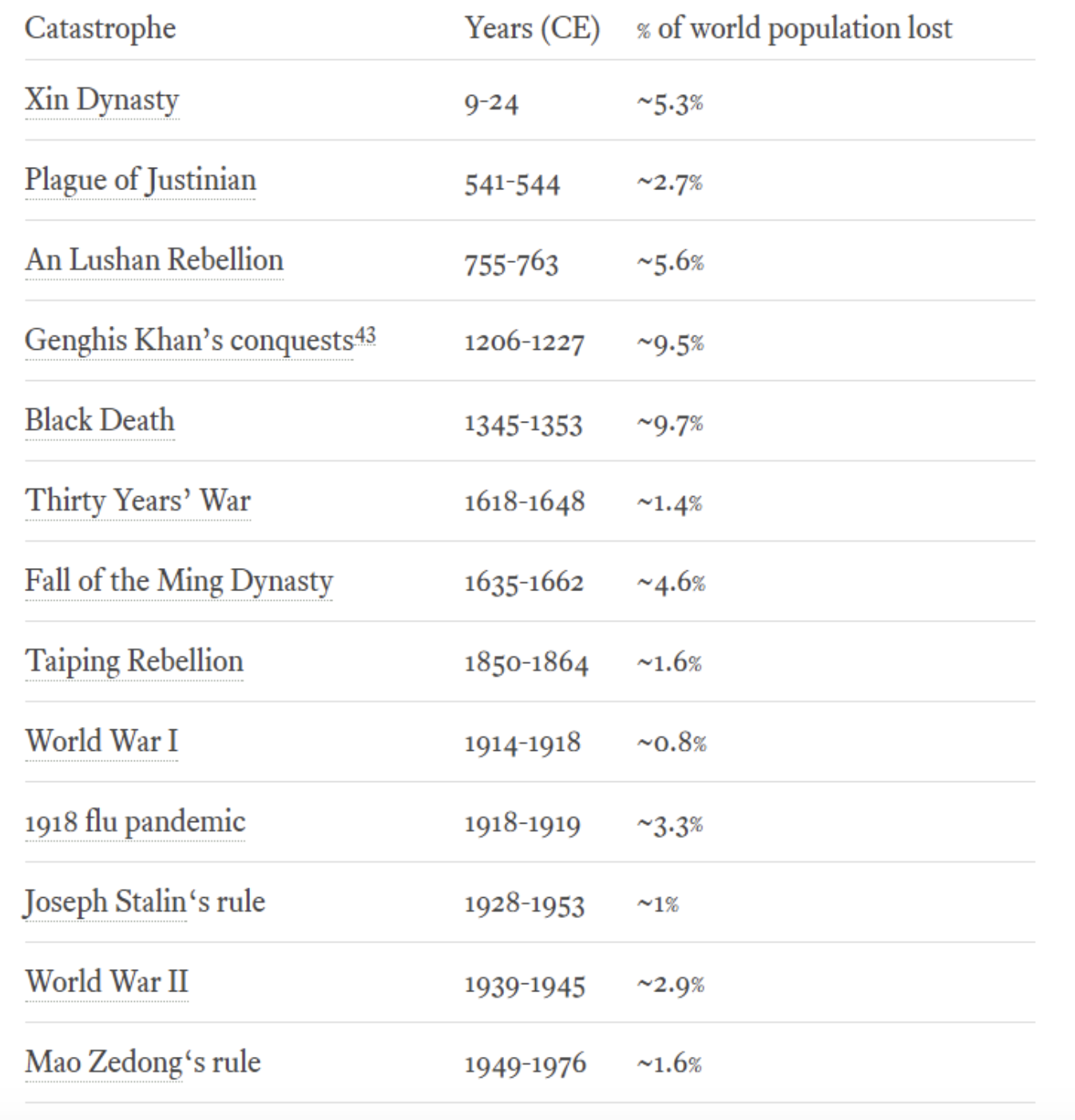

- For comparisons of the deadliest events in history, see Luke Muehlhauser’s survey of the deadliest events in history, also cited in our full profile on reducing global catastrophic biological risks. Note three of the top 10 are pandemics:

↩

↩ - We’ve seen a variety of estimates regarding the chances of an existential biological catastrophe:

- Ord, The Precipice (2020): 3% by 2120

- Sandberg and Bostrom, Global Catastrophic Risks Survey (2008): 2% by 2100

- Pamlin and Armstrong, Global Challenges: 12 Risks that Threaten Human Civilisation (2015): 0.0002% by 2115

- Fodor, Critical Review of ‘The Precipice’ (2020): 0.0002% by 2120

- Millet and Snyder-Beattie, Existential risk and cost-effective biosecurity (2017): 0.00019% (from biowarfare or bioterrorism) per year (assuming this is constant, this is equivalent to 0.02% by 2120).

We’ve looked at the reasoning behind these estimates and are uncertain about which ones we should most believe. Overall, we think the risk is around 0.1%, and very likely to be greater than 0.01%, but we haven’t thought about this in detail.↩

- Gene sequencing, editing, and synthesis are all now possible and are becoming increasingly systematised, making it feasible in principle to engineer and produce biological agents in a way not too dissimilar to how we design and produce computers or other products. This may allow people to design and create pathogens that combine properties of natural pathogens or ones with wholly new features. (Read more)

Scientists are also investigating what makes pathogens more or less deadly and contagious. This improved understanding may help us better prevent and mitigate outbreaks. But it also means that the information required to design more dangerous pathogens is increasingly available.

All the technologies involved here have important medical uses, in addition to hazards. For example, gene sequencing technology may also be essential to help us quickly diagnose new diseases. (See an example of such an advance.) Properly handling these advances may therefore involve a delicate balancing act.↩ - In past decades, genetic engineering could be described as a ‘craft’ that involved a lot of uncertainty, tacit knowledge, and trial-and-error. The ambition of some synthetic biologists (1, 2, 3, and ‘BioBricks‘) has been to make this process more systematic and modular, which would allow more people with less extensive experience to create biological material reliably and economically — more like how we manufacture other products.

There has been steady progress on this front. Innovations in the last decades have made it easier to design and manufacture genetic material. Commercial synthesis is increasingly available and economical. Increasingly large libraries of genetic sequences are available, and sequencing costs are decreasing. Some steps have been taken to manage the risks from this availability, such as screening commercial synthesis orders, though more will need to be done as the industry continues to advance.

Within a year or two of their invention, many cutting-edge advances are accessible to university undergraduates who compete in the International Genetically Engineered Machine (iGEM) competition. The DIY bio movement demonstrates that some advances are accessible to people with no formal training at all (similarly to how 3D printing has increased access to some forms of manufacturing).

Again, it’s worth emphasising that there are benefits to these developments as well as risks. More people being able to sequence and synthesise genetic material means faster progress in a range of areas, such as innovative new drug therapies.↩ - Why would well-intentioned researchers deliberately create unnaturally dangerous pathogens? One purpose is ‘gain-of-function research,’ in which scientists try to increase the contagiousness or virulence of a pathogen in order to better understand its characteristics, including whether particular mutations should be treated as a warning sign if they occur in nature. The result is typically a slightly more dangerous pathogen that’s still well within the bounds of what virologists work with on a day-to-day basis. However, when the research is performed on potential pandemic pathogens, or particularly virulent ones, the potential to create something unnaturally dangerous becomes a concern. The most publicly prominent example of gain-of-function research was a 2011 experiment to increase the transmissibility of avian flu (H5N1) in mammals. The experiment was controversial and triggered a review by the National Science Advisory Board for Biosecurity.↩

- In a 2008 survey, the median expert estimated that there was a 10% chance of 1 billion people dying in an engineered pandemic before 2100, and a 2% chance of an engineered pandemic causing extinction. The authors stress that for various reasons these estimates must be taken with a grain of salt. Nonetheless, arguments like the ones presented here suggest these numbers are relatively plausible.↩

- Luke Muehlhauser’s writeup on the Industrial Revolution, which also discusses some of the deadliest events in history, reviews the evidence on the Black Death as well as other outbreaks. Muehlhauser’s summary: “The most common view seems to be that about 1/3 of Europe perished in the Black Death, starting from a population of 75-80 million. However, the range of credible-looking estimates is 25%-60%.” See footnote 1 for a table of Muehlhauser’s estimates of world fatalities due to different historical events.↩

- In The Precipice: Existential Risk and the Future of Humanity, Toby Ord estimated the chance of human extinction in the next 100 years from a biological agent to be around 1 in 30. Hear Toby discuss this and other potential risks on our podcast episode about The Precipice. See also a critical review of The Precipice, which argues that the risk is much lower.↩

- Here we are presenting the case for working on GCBRs. But of course whether this is the area you should focus on in your career depends (among other things) on your fit for the area as well as how it compares to others you could focus on instead. For example, as Greg Lewis points out, working to increase the chances of safe and beneficial AI seems orders of magnitude more neglected than work on GCBRs, and seems at least as important for safeguarding the future of humanity. This suggests that if your circumstances and fit are equally good for both areas, working to ensure safe and beneficial AI is likely to be the better choice between the two. (Of course, there are many other potential focus areas that might be even better for you.)↩

- The only existing agreement — the Biological Weapons Convention (BWC) — lacks resources and has no verification or enforcement power. (Learn more about weaknesses of the BWC under ‘State actors and the Biological Weapons Convention‘ in our full profile on GCBRs.)↩

- Much has been written on specific technologies. For example, Broad-Spectrum Antiviral Agents: A Crucial Pandemic Tool (2019). A number of the podcast episodes listed above discuss some of the most promising ideas, as do many of the papers in the “Other resources” section above.↩

- Greg Lewis estimates that a quality-adjusted ~1 billion USD is spent annually on GCBR reduction. Most of this comes from work that is not explicitly targeted at GCBRs, but is rather disproportionally useful for reducing them. The US budget for health security in general is ~14 billion. Worldwide the budget is probably something like double or triple that, so spending that’s particularly helpful for GCBR reduction is probably just a few percent of the total; the spending for explicit GCBR reduction would be much less. See the relevant section of our GCBR profile, including footnote 21.

Why might people focus less on work targeted toward GCBRs, even though they are the risks of the worst catastrophes? One answer is that people with the power to allocate resources are not sufficiently aware of GCBRs, or think that they are extremely low. Another answer is short-term thinking: since the technologies most worrying for GCBRs haven’t yet been fully developed, it’s very unlikely we’ll see a biological catastrophe in the next few years; people subject to political and other pressures to prioritise the near future may therefore be less inclined to focus on them. Finally, GCBRs are a type of ‘public good‘ problem, so we generally have reason to expect them to be somewhat neglected. Read more.↩ - How useful more targeted work is for reducing GCBRs vs growing the broader field of biosecurity and pandemic preparedness is a matter of debate. In a recent podcast episode, Marc Lipsitch argued that the best way to address GCBRs may be to simply build up the broader field, because of the substantial overlap between biological threats of all sizes and the tools needed to combat them. In our writeup on reducing GCBRs, Greg Lewis suggested that this strategy — which he calls “buying the index” of conventional biosecurity — would probably be less effective than trying to complement the existing portfolio with work that’s particularly important for reducing GCBRs.

We suspect Greg’s view is closer to the truth, though it’s not obvious, and Greg also expresses uncertainty on the matter. We have a general heuristic: all else equal, a more targeted intervention — one whose primary goal is to make progress on a smaller number of issues — is likely to have a bigger effect on those issues than a less targeted intervention that has more goals. In pursuing the less targeted intervention, you can face more tradeoffs between the different goals, which can reduce your impact on each one considered separately.

Furthermore, with regard to this particular case: the people who have shaped the broader field of biosecurity and pandemic preparedness seem to have generally been optimising for reducing the risks of smaller, more likely pandemic outbreaks. It would be surprising if in doing so they also optimised the field for reducing GCBRs, such that just building the field in general was the best thing someone could do to reduce GCBRs.

That said, because there’s already a lot of support for the kinds of interventions favoured by the broader field, including interventions that do reduce GCBRs, it could in some cases be higher impact to expand the field or in some other way make it more effective at achieving its goals. For example, if you could manage to expand the entire field by 1% in terms of funding and labour, that might easily be better than a more targeted project aimed at reducing GCBRs.

Indeed, Greg also guesses that it’s sometimes better to complement the existing biosecurity portfolio with work that’s especially useful for reducing GCBRs (but which is also helpful for addressing threats of less severe events) than it would be to explicitly target reducing GCBRs. This suggests that the argument for targeting interventions can be taken too far.↩ - How to prevent the next unknown would-be pandemic is, of course, an existing field of research. The COVID-19 pandemic may raise this field’s profile, or it might lower it. This depends on whether enough people are inspired to focus on preventing anything like COVID-19 (or worse) from happening in the future, or if the large majority of people prioritise combating the current crisis. The publication of this New York Times Magazine article suggests that there is mainstream interest in pursuing more broad prevention efforts.↩

- Open Philanthropy generally doesn’t aim to provide 100% of an organisation’s funding, as doing so might make the organisation too dependent on them alone. This creates a need for smaller donors to match or ‘top up’ their funding.↩

- Open Philanthropy is the leading foundation we know of that takes an ‘effective altruism‘ approach to giving. You can learn more about their mindset and research by listening to interviews with current and former research staff, or by looking through their database of grants.

Because of Open Philanthropy’s research capacity, we find that one of the most efficient ways to donate effectively is to simply ‘top up’ their grants — filling the funding gap left by their grants to organisations they’ve selected. Read more about this methodology.↩ - These are the top book recommendations from one of our advisors on GCBRs. We’ve also heard the following are worth checking out for people interested in biosecurity: Germs: Biological Weapons and America’s Secret War; Pandemic: Tracking Contagions, from Cholera to Ebola and Beyond; Spillover: Animal Infections and the Next Pandemic; The Pandemic Century: One Hundred Years of Panic, Hysteria, and Hubris; The Viral Storm: The Dawn of a New Pandemic Age; and Deadliest Enemy: Our War Against Killer Germs.↩